Why do we favor urban real estate investments?

The real estate offerings in our investment marketplace are predominantly concentrated in urban centers like New York City, Philadelphia, northern New Jersey, and select cities in the Midwest and South. We tend not to invest heavily in suburban or rural areas. Why is that?

It all comes down to risk—something that the 2008 mortgage crisis reminded investors to evaluate very carefully before investing in real estate loans. Real estate prices depend a lot on region- and neighborhood-specific factors, which can make it difficult to generalize across “urban,” “suburban,” or “rural” areas. At YieldStreet, however, we have identified many traits of urban areas that make them more resilient to economic downturns than their suburban or rural counterparts. This is especially true of the particular cities in which we offer the most investments.

An economic downturn’s impact on property values boils down to one principle: Your property is only worth as much as someone else is willing to pay. Past trends in home values indicate that when national or even global market downturns strike, properties in many heavily-populated areas with easy access to public transit, retain their value much better than their suburban counterparts. And we have good reason to believe that this urban advantage for investors will persist and even strengthen.

Urban areas and the 2008 mortgage crisis

During the 2008 mortgage crisis and its aftermath, property values in many parts of the United States plummeted. Across many real estate markets, suburban and rural areas were hit especially badly–and urban cores weathered the crisis better. Between January 2007 and 2008, urban foreclosure rates were significantly below the national average.[1] Vacancy rates in 2010 were much higher in suburban and rural communities than in urban areas.

By 2011, the New York Times reported that “drivable suburban-fringe houses” across America were in complete “oversupply,” which would “all but guarantee continued price declines.” Prices fell until they were worth less than they would cost to replace. This left owners, according to the Times, with no rational financial reason to invest in maintenance, let alone improvements. As property prices fell, then, so did the underlying property quality. By contrast, the Times reported that housing in Manhattan and other “center cities” remained in high demand. While jobs disappeared around the country, New York City remained the top destination for college graduates.

In addition to better weathering the immediate impact of an economic downturn, cities also experienced faster post-recession growth. The Housing Assistance Council noted this divergence just a few years after the crash, finding that non-metro housing prices had continued to decline in 2010 while metropolitan prices had stabilized and begun rebounding.

Philadelphia and New York–two places where YieldStreet frequently offers real estate investments–were among the metropolitan areas with the starkest divergence between urban and non-urban prices. As of a 2017 report, Philadelphia’s housing values in Center City had surpassed pre-recession levels. The median home-sale price rose an average of 8.6 percent per year between 2012 and 2017. By contrast, during that period news reporters described Philadelphia’s suburbs as “limp[ing] along” with “near-negligible” price increases. New York City’s downtown area similarly outperformed its suburbs in post-recession real estate prices. By 2016, The Atlantic reported that “prices are rising and homes are sold within days of listing”—in stark contrast to New England’s suburbs, where “[t]he number of days homes stay on the market has increased, and people are getting so desperate they’re renting out their homes.”

Reasons for resilience: Diversified Economies

Urban areas’ relative resilience during and after the 2008 economic crash was not a stroke of good fortune. It was the result of some inherent common characteristics of urban areas.

First, urban areas tend to have more economic diversity than surrounding suburbs or further-out rural neighborhoods. Economic downturns do not affect every industry equally. Insulated or resilient sectors can help make up for those that are hit hardest. In Philadelphia, for example, employment in the city’s education and health services industries actually grew during the recession, allowing the city to retain jobs despite declines in other industries such as finance and information services. In New York City, property owners retained liquidity—the ability to pay back debt with cash on hand, thus avoiding foreclosure—because of, according to Moody’s, “its vibrant economy, diverse tax base, and a labor market which recovered quickly from the recession as jobs were added across a range of sectors.”

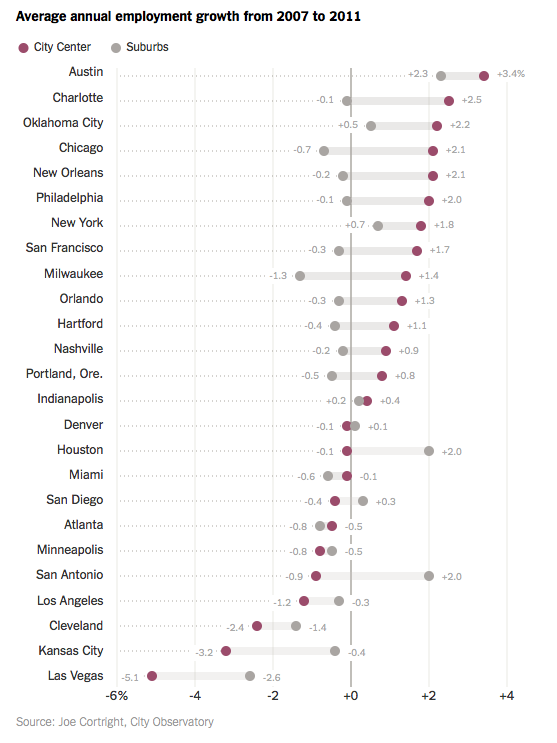

The New York Times broke down this trend further, mapping job growth between 2008 and 2011 by city, and found that city centers overwhelmingly outperformed their suburbs. As shown in the chart below, New York and Philadelphia are among the cities where urban job growth most exceeded suburban growth. According to one up-close account of Philadelphia, while incomes in Center City Philadelphia grew, they fell in about 75 percent of surrounding suburban neighborhoods in Pennsylvania and Southern New Jersey. This meant urbanites had a greater ability than their suburban or rural counterparts to lease and buy homes, upgrade owned properties, and support nearby businesses that in-turn rented and invested in real estate developments.

Reasons for resilience: High Prevalence of Rentals

In addition to broadly diversified economies, urban areas have more diverse housing options—including a higher prevalence of rental properties. According to the latest American Community Survey, homeownership rates increase with rurality. 59.8 percent of homes in urban areas are owned, compared to 81.1 percent in rural areas.

The positive benefits of rentals during an economic downturn are twofold. First, suburban and rural homes are more vulnerable to foreclosure than urban properties. Second, rentals result in a more flexible workforce.

Urban residents’ lower vulnerability, in aggregate, to foreclosures is in some ways a simple numbers game. Because there are fewer home mortgages relative to population in urban areas, there are fewer per-capita foreclosures. Moreover, specific characteristics of suburban and rural mortgages make them particularly risky. Suburbs were the stereotypical site of new, large “dream homes” in the build-up to the housing crisis—homes that pushed the limits of loose lending practices and resulted in many Americans buying more property than they could actually afford in the long term. When the economy turned downward, these homeowners could not afford their monthly mortgage payments nor find renters who could. In rural areas, pre-fabricated homes are particularly popular. These homes are often financed with personal property loans, also known as “chattel loans,” instead of with traditional real estate mortgages. Chattel loans involve lower down payment costs and higher, more expedited payments—making them harder to keep up with when financial hardship strikes. And suburban and rural vulnerability to foreclosure does not just put individual property holders at risk. Instead, foreclosures pull down prices across their local markets. Properties across urban areas, then, tend to be better able to retain their values during market downturns than those in places with higher foreclosure rates.

The second benefit of urban areas’ relatively higher proportion of rented versus owned homes is a more flexible workforce. Homeowners who lose their jobs may, in short, get stuck. In the midst of the recession, the New York Post offered Detroit’s suburbs as archetypal problem areas where “people can’t move to where the jobs are because they can’t sell their worthless homes.” As a result, the local economy stagnates. In a recession-era foreclosure auction near Detroit, the Post reported, “many seized properties listed in a phonebook-sized directory drew no bids whatsoever.” This magnifies the impact of economic downturns in rural and suburban areas, because their residents are faced with a catch-22 of either paying for two homes or staying put without a job. In urban areas, renters who lose their jobs are free to end leases and chase new work to other parts of the city.

Resilience in the Future

Economic diversity and lower instances of home ownership are flagship features of cities that we believe will continue to make urban areas attractive for real estate-related investments. Trends suggest that urban properties’ buffer against economic downturns will not only persist, but may even strengthen. Put simply, as baby boomers retire and millennials enter the workforce, they are moving away from suburban homes and college campuses into city centers. They bring resources with them to stimulate the urban economy, and businesses follow in order to recruit and retain young workers. Economic diversity and demand for housing—including a relatively high demand for rentals versus owned properties—strengthens accordingly, thus strengthening the factors that contribute to urban resilience.

YieldStreet will continue to invest in real estate in America’s urban centers. While we hope that a recession in the magnitude of the 2008 housing crisis will never happen again, we know that the economy’s future can be largely unpredictable. Rather than trying to perfectly predict market fluctuations, we and our investors take comfort in believing that our real estate portfolios may remain relatively resistant if downturns do occur.

[1] Michael D. Webb & Lawrence A. Brown, Foreclosure, Inequality, and the Difference that Place Makes, Rural Sociology (2016), at 15 tbl.1.

This communication and the information contained in this article are provided for general informational purposes only and should neither be construed nor intended to be a recommendation to purchase, sell or hold any security or otherwise to be investment, tax, financial, accounting, legal, regulatory or compliance advice. Any link to a third-party website (or article contained therein) is not an endorsement, authorization or representation of our affiliation with that third party (or article). We do not exercise control over third-party websites, and we are not responsible or liable for the accuracy, legality, appropriateness, or any other aspect of such website (or article contained therein).

What's Yieldstreet?

Yieldstreet provides access to alternative investments previously reserved only for institutions and the ultra-wealthy. Our mission is to help millions of people generate $3 billion of income outside the traditional public markets by 2025. We are committed to making financial products more inclusive by creating a modern investment portfolio.