In the first of two installments, five industry professionals speak to Yieldstreet about why art is selling at historically high prices.

Key takeaways

- Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips reported a record $15 billion in art sales last year.

- The contemporary art market saw a record-breaking $2.7 billion in sales in 2021.

- Art professionals attribute the sales to ‘a huge amount of cash’ flowing into the market.

In the early months of 2021, a 359-page report released by Art Basel and UBS Art Market, the Swiss multinational financial services company and one of the largest private banks in the world, offered the most exhaustive analysis of the coronavirus pandemic’s effect on the international art trade. Neither the findings of the author’s forecast were optimistic. Combined dealer and auction house sales of art and antiques totaled $50.1 billion, down from $64.4 billion in 2019— their lowest level since the 2009 financial crisis. In an interview with the New York Times, the report’s author, Clare McAndrew, said that she did not expect the art trade to return to anything resembling normalcy in the near future. “I see this as another transitional year,” she said of 2021. “I suspect we may see more businesses in trouble.” What transpired though, was—to put it mildly—surprising.

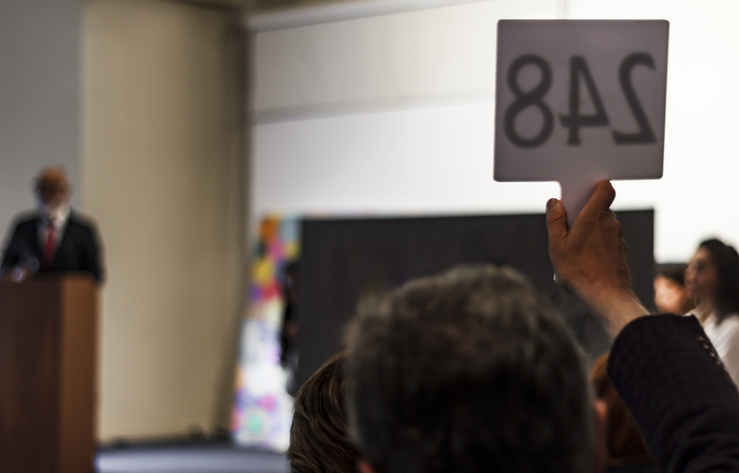

The Big Three auction houses (Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Phillips) hit a record $15 billion in sales. By October, Artprice released its annual report, noting that the contemporary art market had experienced a record-breaking $2.7 billion in sales at auction with a record number of artists (34,602) accounting for a record number of transactions (102,000) in a period of 12 months. “We sold art like the Titanic was sinking and the sky was falling,” an anonymous gallerist told Yieldstreet. So what’s behind the unprecedented numbers?

‘A huge amount of cash’

It all begins with the surge in global wealth during the pandemic. “There was a huge amount of cash flowing into the market, so much liquidity and money readily available at historically low interest rates,” says Yuki Terase, a founding partner of art advisory firm Art Intelligence Global. “Our clients, in general, managed to increase their assets multiple times over [during] the last two years. Inflation was happening and they found that the value of the cash was decreasing. So a lot of money flew into art.”

Yet as Terase also notes, conversations surrounding art collecting simultaneously shifted. While some clients continued collecting art for the sake of the art itself, others sought art as a way to diversify their assets—and they spoke about this motive with a kind of transparency that had previously not existed. “Before the pandemic, talking about investment values and returns was almost forbidden,” notes Terase, who heads the firm’s Hong Kong headquarters. “Now you see it in the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal. Even specialists are starting to say things like, ‘This period compared to that period is undervalue.’”

For Lauren Kelly, director of Sean Kelly Gallery in New York, the surge in art sales was intertwined with the fact that people stayed home. “With everyone spending so much time at home over the past few years, it’s made one think about the artwork they live with,” she says. Collectors, unable to travel the world as they once did, continued to experience beauty in a new dimension through the works they acquired and brought into their spaces.

As galleries and auction houses adapted to the limitations of COVID-19 by implementing things like online viewing rooms and virtual art fairs, collectors at large also became more comfortable with buying works virtually. “There used to be this need to see artworks in person,” says Patrizia Koenig, the 20th Century & Contemporary Art Specialist for Phillips. “People would travel all over the world to fairs, to auctions. I think while that’s still really important, and nothing is as great as seeing an artwork in person, there has been a change in that some collectors are more comfortable buying works unseen.”

‘Selling to a tech-savvy crowd’

And it’s precisely this shift—the ease with which people are buying art online—that industry experts unanimously agree has played a significant role in the art market’s boom.

Eleven percent of all auction sales in 2021 were online, a 28% increase from 2020. “Online bidding seems really intuitive now and it seems crazy that this would have not been the case before, but I think even back in 2014, people were like, ‘This is never going to be something we’re implementing.’ The art world was very traditional in its ways,” Koenig says. “There needed to be a bit of this crisis moment for innovation.”

Caspar Jopling, the Head of Strategic Development for White Cube Gallery in London, notes that the confidence crisis amongst the collecting community, driven by a lack of market information at the beginning of the pandemic, was quickly remedied by adapting to digitally-driven methods of offering artwork to clients. “This digital shift also helped accelerate the art world’s increasing transparency by giving collectors a greater context into which they base their collecting decisions,” he says.

The great digital migration has brought with it an entirely new demographic of buyers, too. If online sales pre-pandemic were once seen as being reserved for things that, “weren’t good enough to go into real, live sales,” Terase says, “Now, people are strategically selling certain things targeted to a young, tech-savvy crowd who are in their 20’s and 30s’ and would much rather go online.” The pivot has proven particularly advantageous for Asian clients, a sector that has radically impacted the art trade market over the past two years—and a sector that Part II of our Art Research Deep Dive will further mine.

Learn more about the ways Yieldstreet can help diversify and grow your portfolio. Investing in art is so easy with Yieldstreet today.

What's Yieldstreet?

Yieldstreet provides access to alternative investments previously reserved only for institutions and the ultra-wealthy. Our mission is to help millions of people generate $3 billion of income outside the traditional public markets by 2025. We are committed to making financial products more inclusive by creating a modern investment portfolio.